Put Your Stories on the Map

Sharing Stories Over the Fence

Stories orient your community from its past into the future.

Narrative Infrastructure, the stories hidden in your city can help guide your decisions.

Have a read of some of the stories from Famagusta by clicking on the map.

Select your group below to learn how Narrative Infrastructure can help you.

Sneak to School

I would walk through the moat and dodge the traffic. There was no real traffic then, but anyway. From there I would pass over into Akkule and from there straight on to the Gazi Primary School. The elders of our neighborhood later told us not to go from that route.

Death at the gate

I also remember that after 1963 - you remember the two Greek Cypriots who entered through the port gate – back then I had a classmate; Mr. Selçuk the police commander. His daughter was my classmate back then. I was in their house. Whenever anything happened he would always come and tell us anyway because we lived within the walled city. So I was there and her father received a phone call that something had happened. He said, “Come on quickly girls, we are going to go to the walled city.”. So we went. Nobody was actually allowed within the walls but because he was a police commander we were able to get inside and I saw those two Greeks lying on the ground. I'll never forget it. On the floor at the entrance of the Famagusta Gate.

A Young Man Called Tarzan

"There was a young man called Tarzan -the other night I found a picture of him on someone’s page and I kept it for myself – he later died in Belgium. Master Yüksel made a deal with him. This young man was accused of spying for the Greeks. However, this was not true. It was actually the opposite."

"Yes. This boy was accused. They tied Tarzan's hands and feet in chains and hung a sign on his chest that said 'This person is a traitor to his country'. Tarzan let all of this happen. He was then carted around Famagusta with a police escort as a traitor."

"Let's get back to Tarzan. So they took Tarzan around in this way. As our side expected, the Greeks did have many spies here. They even had a spy in our police force. I brought that man to the authorities because I was the company commander of the Foundation Apartments division near Namık Kemal Highschool. This spy came with his weapon and surrendered to us. When he came to us he said that they were going to kill him. He had his weapon with him. I was the company commander of that area and he surrendered to me. We took away his weapon and escorted him to the Famagusta police. They kept him there. Afterwards they made him the coffee maker for the police. He also married a woman. He remained there for years."

Blind Hüseyin Gets Lost

There was a shepherd in our village called uncle Hüseyin, he was missing an eye so they called him Blind Hüseyin – this should be around 1962 if I'm not mistaken – he came to the village in a panic and said, “I went to Famagusta and I nearly lost my way!” They asked him what happened and he said that they had changed the Famagusta gate so much that he almost didn't recognize it. I think they made a new road entering Famagusta and he didn't recognize it so he gave us this news in a big panic.

Faux Historic Land Gate

When the builders were constructing these areas they made those indentations to make it look like the original structure. On the left hand side of one of those entrances you can see one of the original gates, The Asmalı Gate. They tried to make it look like it. When you look at them at a glace, the tourists cannot differentiate between them. They think it's new. Yeni Kapı was built after the 60's. The inside of it is all plastered with concrete. They can tell the difference there. However, the three gates made at the harbor and the Cambulat gate were made so well that you might think they were the original Venetian or Lusignan structures.

Gecco's Gold

"Do you know what was found there at the walls. Look- Hasan Dama, my aunt's son – not the Hasan Dama that you know who is my cousin, but the one who is his uncle. Do you know the house of Sinan the dentist? When you go up from the house of Sinan the dentist there is a big hole there and when you walk from there towards Akkule there are embrasures. At the very first embrasure you come to we were chasing a gecko. The gecko ran behind some plaster in the wall. He broke off the plaster with a rock. Lying there was a pouch full of gold."

"Wow. I'm going to start following geckos from now on."

"We discovered a pouch full of gold. So, what is this? Similarly, in 1974, the Greeks would hide their valuables around Varosha intending to get them after they returned. It is said that these items are buried or hidden using a certain cypher like they used in ancient Egypt. As I said one of these was the pouch we found. There was nothing much left of the pouch but the thin pieces of gold were there alright. A handful of them."

Fell Off the Wall

"We didn't use the door looking to the sea. Why? Because our business was on the upper side. That's why we used this door [points at document]. There's a door here [lifts up map] and we would go through that and go to school. We would come back the same way. One day we were returning from school and when we came to the door we realized it was closed. What were we going to do? How were we going to get home? There were these 5th and 6th year students (our elders) and they said that they would climb through the grills. They managed to get down. They were slightly bigger than us and these grills were 1.5- 2 meters up. They managed to get down from there using the corners of the walls somehow and went home. They returned with some rope. They threw it down to us. One by one, we tied ourselves to the rope and they pulled us up through the grill and let us down on the other side."

"So you managed to get home?"

"Yes. As I was descending (I was probably a bit scared), instead of saying, 'Lower the rope' I shouted, 'Give me rope, give me rope' and the rope broke. So I fell to the ground. Our friend was upset of course. I had nothing broken.

"Years later, I visited a doctor because I had some leg pain and he asked me if I had had any previous accidents. I replied that I had not. Then I remembered and I told him about my fall. He said there is a lump in your knee. I also noticed later that I might also have a problem with my shoulder because I find it difficult to move and I suspect there is some calcium build-up."

"Well there is also a case of old age so they probably cannot pin-point the real reason. He'll blame the fall for everything now. 'He fell off the wall.'”

Girls Upstairs at Cami

"When Ahmet Sedat was young he was a muezzin here. His Aunt and her husband didn't have children. His father was a horseshoer (blacksmith?). His aunt's husband taught Ahmet Sedat, his sister Mrs. Hava, Erdoğan Celal, Mrs. Havva's daughter, Emir and the rest of them how to read and write old Turkish. Because Ahmet Sedat had a nice voice he trained him as a muezzin. On Friday prayers and on the bayram prayers – you know where the muezzin is, it has a second level – that second level is where the muezzins would be on bayram. When we were in first year – in 1954 I was in the first year – we were obligated to go to the mosque on Fridays up until we were in the first year of high school. The closed area was for women. But the young girls would go up to that second level where the muezzins were. The muezzins would only go up there on bayrams. Usually the girls of Namık Kemal high school would go up there. Sedat would be on the lower level. We had people with very powerful voices. There was Öner efendi. Öner Efendi is Hüseyin Akil Hoca's uncle. There was Hüseyin Akil efendi. There was the imam, Ibrahim Sıtkı efendi. There was his son, Mustafa. He was also a muezzin. There were three muezzins. Ahmet Sedat would get among them as a young one. I was two years younger than Ahmet Sedat. From the third year of primary school onward we would go to the mosque."

Mustakya's Telephone

"Most importantly, in front of them was uncle Mustakya's house. Why was he important? Because he was part of the history of Famagusta. None of these people are left anymore. Master Havva left us a little early. She was a very respectable person and looked after herself very well. Remember we said that Hasan Kürpat had the only television? Well uncle Mustakya had the only telephone in the neighborhood in his house. My sister would call us from Nicosia and my mother and I would run to uncle Mustakya's house to talk to my sister. Because my sister couldn't come to see us from Nicosia and we couldn't go and visit her either. Those years were problematic as you know. So we kept in contact with uncle Mustakya telephone."

"You couldn't call directly in those days. You had to call the central and you also had to know Greek. You then had to ask to be connected to the number you were trying to call and only then would they connect you. Then you would have to wait for 15 minutes to half an hour before you could talk to whoever you were trying to call."

Ottoman General's Head Flew Off

"So when relating the facts, of Cambulat for example, you can add that there is also a legend attached to it. For example, to breach the walls the Ottoman general jumped into the cogwheels and his head flew off but he caught it and put it under his arm and kept on fighting. This is a legend, hearsay. It's like putting ketchup or mayonnaise on something."

Old Gate at Othello

"Namık Kemal mentions in his book that it had a beautiful sea and he mentions that he would frequently go by the sea. The people would pass through Othello, there used to be a gate there. There was no hole before. I remember that I used to pass through Othello on the back of my father since the door was usually closed. Namık Kemal also mentions that there was no harbor back in the period. Englishmen built the harbor."

"Yes, I think that’s because English damaged the places when they opened the sea gate here and the other gates there."

"Ever since I could remember, there was the Hole there. I don’t know how you could pass through except the Hole."

"They even opened two gates there. We would crawl before, later they were enlarged. One side was for women and the other was for men."

"But also, there were some women who would come to the men’s side."

Saboteur Headquarters

"That young man was from Mersin but he had come to Cyprus a long time ago and had settled. He was going to get married. So about Tarzan, I'm talking about 1966. Tarzan was brought up to that Kara Kapısı and was thrown of from the gate with his hands and feet tied in chains. They tried to make it look like he tried to run from the police. He went to the Greek police in order to take refuge. This was a few weeks after he was paraded around town. The Greek police accepted him. They kept him away from the Turks. From that moment on he started to send information to us. The saboteurs would use the information he sent. The headquarters for the saboteur team was what is now used as changing rooms for Türk Gücü. In order to become a saboteur you needed to have physical prowess, you needed to be strong, you needed to be agile. Not everybody could be a saboteur. Therefore, most of the members of the saboteur team were the football players in Türk Gücü. They already had physical training and were strong."

Süt Arkan: Mother's Milk

"Which is this; it is said that if mothers who had just given birth and could not produce milk went to Süt Akan and rubbed the water on their breasts they would start to produce milk. This is a legend."

Getting Ice for the Merkez

"Uncle Behiç would buy thin paper and fold it to make his coffee packages. He would use an oval stamp to place his trademark on them. These came in different sizes. He would seal them with staples. Uncle Behiç had a round fridge where he'd put the sodas and water and then he'd place block ice on top that he would break down. The sodas back then where in bottles and both the sodas and the water would get cold. He'd serve water with each coffee of course. Later on uncle Behiç started to buy a lot of ice and sell it to other. Because I used to help him sometimes he took me along with him to the ice factory to buy ice once. The ice factory was behind where the co-op sells their juices now. So we went there and bought 5-10 pieces of ice. When he brought them back he would cut them into quarter pieces and half pieces to sell them. People would also take them home with them. were a couple of people who smoked hookas also. Uncle Halil and uncle Ahmet. I remember them smoking very clearly."

Preoccupied Scientist

"Mugagkak used to have his hair cut in Sıtkı's Barbershop. I was a child back then. In our neighborhood. He would always wear a fedora. Once I saw him after he had had his haircut. He got up and put his hat on. At first, he wore it correctly. Then he took it off and wore it backwards. I thought about it later."

"Why did he do that?"

"You know that certain scientists are always preoccupied with other things and their minds are always elsewhere? They say that Einstein would write equations all over the milkman's cart. He wanted to represent himself as a great scientist. Tourists would come here and think, 'What an eccentric man?'. You'd think his bicycle would collapse any minute.

"Of course, his knowledge on the history of Famagusta was indisputable and his ambition was to keeping Famagusta as it was. That's why he couldn’t get along with anyone in Famagusta because he wanted to preserve the city just the way it was and these effort would have displaced everybody from their homes. No one liked him. These things were not possible."

"He would deliver small glasses to the English and as he was taking these he would give us coloring books, coloring pencils rulers..."

"Was he a missionary, did he belong to a special group?"

"He was Assyrian. However, the English had certain people who would do that."

Local Voices, Real Impact

Isolation and impersonal data are silencing citizen voices, erasing local identity. Narrative Infrastructure pushes back by mapping community stories. We turn oral histories into powerful tools, ensuring development respects local roots.

Built-in Continuity

We want communities to lead with the stories of their residents. We aim integrate the stories of the community with research, policy, and development through the medium of Geographic Information System (GIS) to create a world-class qualitative research infrastructure with unparalleled cross-cutting capacity.

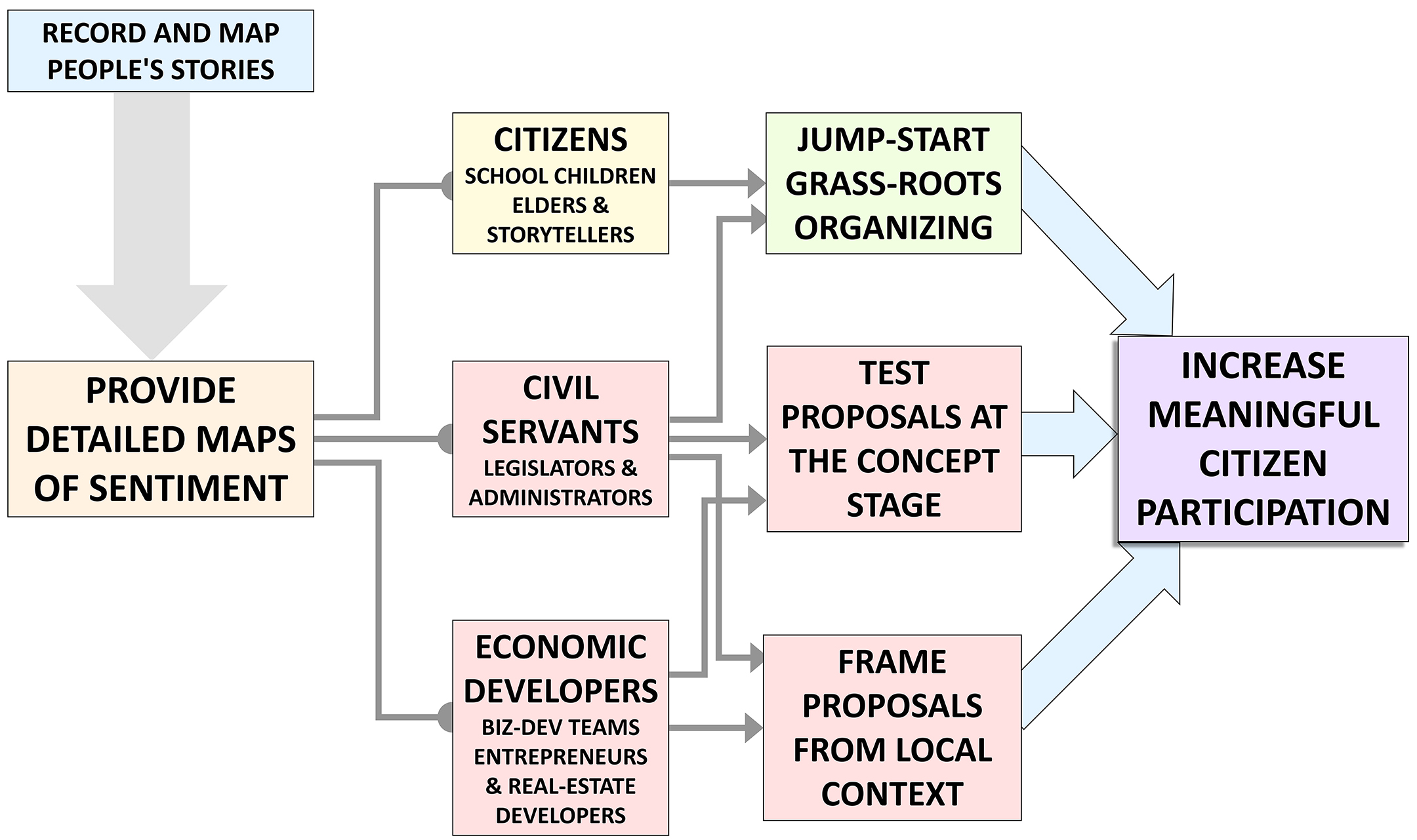

How Community Stories Help Meaningful Citizen Participation

About our vision

Narrative İnfrastructure focuses on existing neighborhoods and helps them recognize and reinforce their informal traditions. Developers and politicians can use community story maps to enhance continuity with projects, contextualizing new initiatives with the local sense of identity. We do this by recording and mapping the oral history stories of the neighborhood, and looking for patterns in the story themes that can be incorporated and expanded upon.

About our mission

We want communities to lead with the stories of their residents. We aim integrate the stories of the community with research, policy, and development through the medium of Geographic Information System (GIS) to create a world-class qualitative research infrastructure with unparalleled cross-cutting capacity.

See What We Offer

See What We Offer

Empower Neighborhoods

Demonstrate the co-location of history to living memory and contextualize the newcomer’s experience.

Business Risk Mitigation

Frame new ventures in continuity with community memory: Leverage continuity with the past when creating the future business plans and public agendas.

Engage Civil Society

Narrative İnfrastructure enhances participatory democracy through contextualized preservation of public input so it can be reused. We identify cultural boundaries as opportunity zones for peace-building. Blunt opportunism and ensure the local stakeholder has a degree of agency.

Human Scale of Local Policy

Narrative İnfrastructure is a method of channeling the informal knowledge of the past into the formal planning of the future. We integrate with bureaucratic GIS systems, providing the location of sentiment. Challenge conclusions derived from Big Data and large statistical sets applied to local contexts.

Training

We can train your community group, students, or stakeholders how to collect and map oral histories.