Policy Proposal |

Narrative İnfrastructure |

||||

| Issues: The sense of citizen agency is in decline |

|||||

| 1. |

Individuals are increasingly isolated from social interactions and local political interactions even more so. If they ever act politically, it is usually on a discreet issue. |

||||

| 2. |

Economic and policy proposals are largely built on statistics based on large groups, which rarely reinforce local character. In response, locals are disinclined to support such proposals. |

||||

| 3. |

Due to the increasing adoption of location-independent digital socializing, the experience of diversity within our own communities has lost its primacy. This reinforces segregation by class and race, unraveling our inter-reliance. |

||||

| Aspirations: Tell our stories for long-term impact on multiple issues |

|||||

| A. |

How wonderful would it be to tell your individual story and effect how we all manage our common affairs? |

||||

| B. |

How wonderful would it be to act in your community and have little fear of being attacked or insulted? |

||||

| C. |

How wonderful would it be to know your personal history means something to your community and is a building block for new proposals? |

||||

| Approach: Map community members’ stories |

|||||

| To get anything done together, we have to tell a story to one another. We are more convincing and when we speak from our lived experience, and then others are more likely to respect our point of view. Others may agree, or they may disagree with our conclusions and offer their own story. Together, we can find common themes that we can agree to be the basis for changes (or for deterring changes). |

|||||

|

|||||

| The experience of freedom arises from engaging with fellow citizens in meaningful ways. To be full of meaning, our words and actions need to influence others and be influenced by each other in our common effort to maintain the human world we share. We can have different truths—different faiths and different upbringings—yet we can share in each other’s successes and support each other in challenging times. When we share our lived stories, we have a higher chance of being able to relate to each other’s common experiences of being human. Rather than being distracted by our differences, we can develop understanding of our shared struggles and joys. | |||||

| Narrative infrastructure is built from the stories of people on the land. Stories explain why things mean what they do. Every new road has a story—usually a promise of prosperity. Every new regulation has a story—usually an instance of trespass. Every repair requires a story of sustainment and revitalization. In this built world, everything around us has a story. This is the narrative infrastructure: the unseen structure of our communities. | |||||

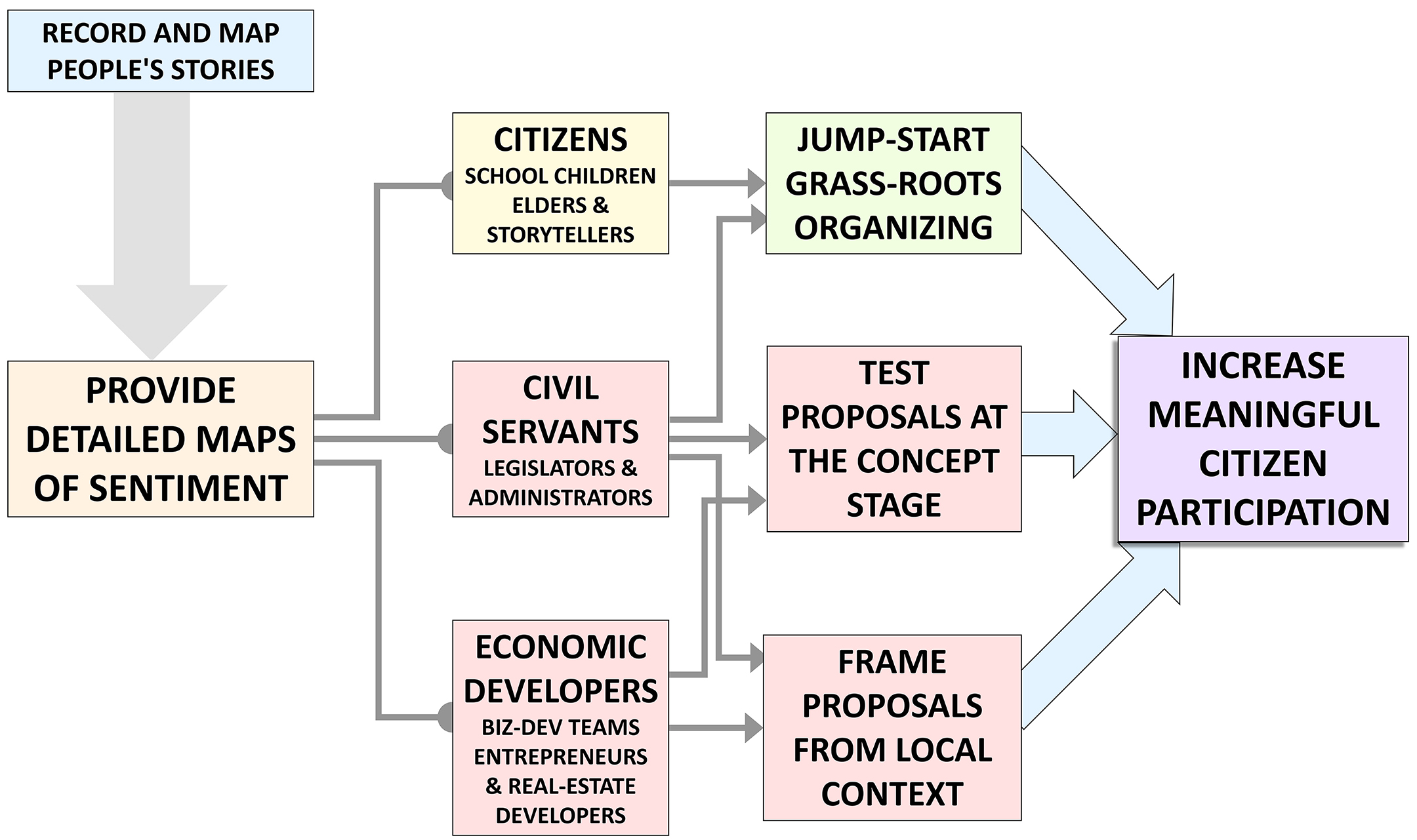

| What if we could see that structure? | What if we could see that structure? We could change how we manage our communities. Too many times, we make proposals for change and continue many months into a project before an unknown stakeholder steps forward to complain that the project is an insult to their story. If all stakeholders could record their stories in a visual format that maps to the land, then any new proposal could address the lived experiences of the community from that specific location. The stories are all there, they just need to be mapped. | ||||

| Influence countless future developments and decisions | Stories are mapped to the location described in the story so they can influence countless future developments and decisions in their proximity. When you tell a story about your experience on the land, the land holds your memory so others know what that land means to you and those you influence. When we look for common ground, we should look at our mapped narrative infrastructure, and tell new stories together. | ||||

| Enhance the agency of individuals in their community | This proposal for a public narrative infrastructure (Nİ) enhances the agency of individuals in their community by providing a digital platform for the long-term storage and easy dissemination of their stories. The developers of this proposal urge the building of narrative infrastructure as a public infrastructure based on the principles of free political speech without influence from for-profit interests. This infrastructure can serve every member of communities where it is established, and it can be improved incrementally by locals on an on-going basis. Communities need a technical solution to begin recording their narrative infrastructure and a governance structure that ensures the unbiased archiving of their speech. | ||||

| The following is a brief discussion of what narrative infrastructure looks like and how to build it. We conclude with a call to action publicly fund this essential public infrastructure. | |||||

| What narrative infrastructure looks like: Detailed maps of sentiment | |||||

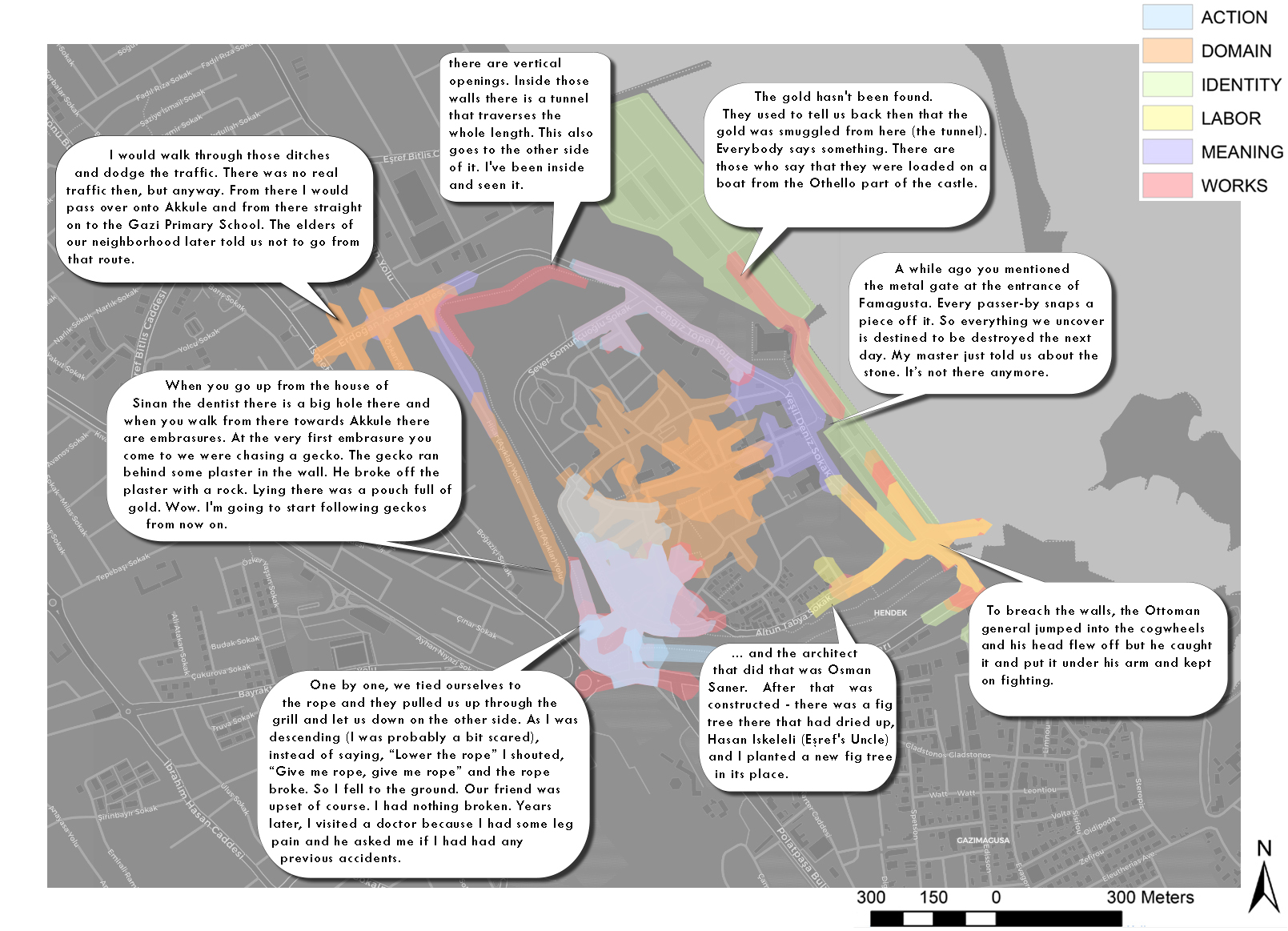

| When we gather stories from people, the story includes mostly subjective information that describes the teller’s beliefs and emotional attachment. Stories also include temporal and spatial data. Using digital maps, we can now show where different parts of those stories took place and demonstrate the area of affect for that story: | |||||

| Example of Nİ from Famagusta, Cyprus | |||||

| How the stories overlap with each other or other mapped data (such as demographics, transportation, environment, and more) contextualizes neighborhoods for policy makers, regulators, and economic developers. When gaps appear in the Nİ, that is either indicative that there are too few stories collected or that the area has no emotional investment from the community. | |||||

| This layering of data allows us to use narratology to developing proposals for blank areas of the story landscape. Nearby stories can be analyzed for themes and then mixed into a new proposed story for the space lacking community narratives. This storytelling method leverages local stories as the starting point for proposing community change. Whatever the social or economic goal, the core of the proposal will garner local support by building continuity with lived memory. | |||||

| Building Narrative Infrastructure: Gather, Process, Archive, and Govern | |||||

|

|||||

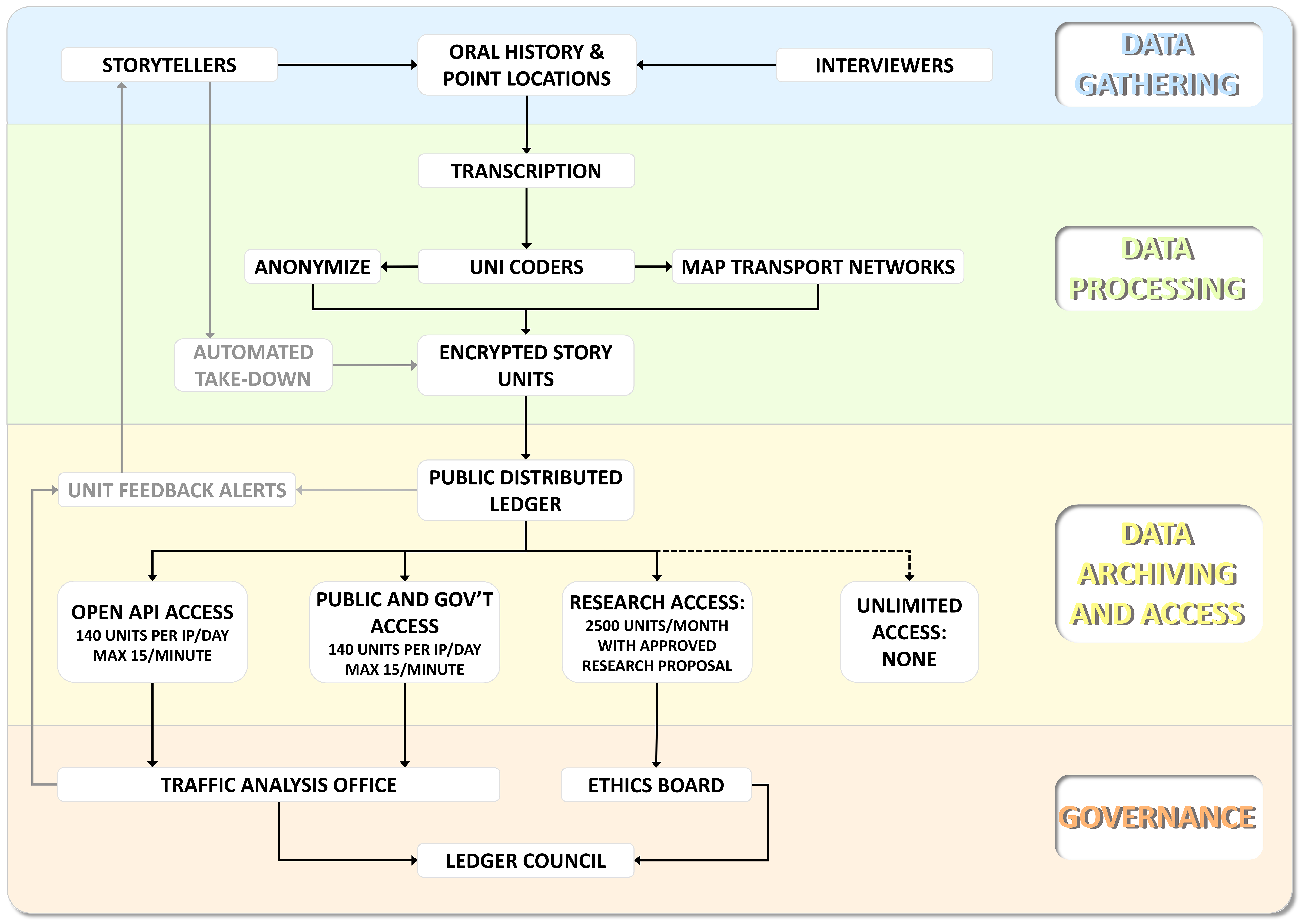

| Data Gathering: | |||||

| There are three data sources for building narrative infrastructure: | |||||

| 1. | Large archives of oral-histories are stored in libraries around the world. Processing these from text, video, and audio format to the visual format (maps) is an easy way to quickly populate large areas of the Nİ map while simultaneously leveraging the embedded value of those archives, which is currently inaccessible. | ||||

| 2. | Community members can contribute to Nİ by conducting interviews. Many amateur organizations already exist to share stories. Given a few common tools, they can regularly add new oral-histories to Nİ. Middle school students conducting interviews of their grandparents for a class can become Nİ contributors. When an elder sits down to tell their stories, a tablet computer can turn their stories into narrative infrastructure. | ||||

| 3. | Public engagement efforts are already required to be conducted on behalf of publicly funded projects and policy proposals. With a few adjustments to the professional practices of collecting citizen input, that data can become narrative infrastructure. That same public contribution can then impact not only the issue that inspired the community members to get involved, but future issues that may impact their lives. | ||||

| Data Processing: | |||||

| There are four tasks to processing oral-histories into narrative infrastructure: | |||||

| 1. | Transcription of the storyteller’s words is the first step to breaking an oral-history into ‘units’ of stories that are specific to particular locations. For several languages, this process can be automated with only a follow-up readthrough necessary by the storyteller to catch transcription errors. For other languages, either the interviewer or researcher/interviewer needs to transcribe what they record. This can be done by anyone who is fluent in the storyteller’s language, and so could be a contracted transcriber. | ||||

| 2. | Anonymization of the data is required if the storyteller has requested to remain anonymous or to keep characters in the story anonymous. This can be done by the interviewer and then reviewed by the storyteller to ensure no one in the story is at risk because of the things said. Alternately, after the interviewer has the transcript and has broken the story into spatial units of text, these can be distributed by the UNİ Coder System to different coders around the world in different universities. Each story unit will then be given substitute proper nouns for people that do not match the other story units, breaking the identification link between the story units. The stories will still be related at the macro level only by the intellectual property rights access code possessed only by the storyteller/archive manager. | ||||

| 3. | Mapping the story units requires more than addressing them with latitude and longitude coordinates. The interviewer and storyteller will assign the initial address, but those coordinates are “point data” like a pin on a map. Because points cannot reveal overlap, Nİ requires the stories to be assigned to an area. The baseline area of effect is calculated at 220 meters from the pin. So, if a story takes place at a crossroad in an empty piece of rural land, the story effect area would be a cross of 440 meters along one road and 440 meters along the intersecting road (plus 10 meters to each side of the roads). These numbers are based on contemporary research of human memory and typical visual range. To account for spaces with more diverse transport networks, it requires that local Geographic Information System maps include segments and intersections for each road or path in the story’s vicinity. This is not a complicated operation, and for most municipalities with a transportation department it is already complete. If not complete, an hour or less of mapping is required per story. | ||||

| 4. | Encryption of the story units is the final step before archiving. This ensures that the data is secure and verifiable to prevent manipulation of the story content. | ||||

| Data Archiving and Access: | |||||

| At the core of the narrative infrastructure archive is a Public Distributed Ledger. Ledger members are selected by the Ledger Council, and are granted funding to support the storage and distribution of the story archive. These institutions keep copies of each other’s data in different countries, under different laws, and outside of any one political sphere of influence. This allow any misuse of the story units to be flagged as fraudulent by the Nİ system. The ledgers will have three levels of access governed by the Ledger Council: | |||||

| 1. | Open API Access is made available to third parties to leverage the content of the archives for applications like walking tours, browsing local stories around a specific business or landmark, or to consolidate the stories involved in a particular political proposal or economic development project. This access would be granted up to 140 story units per day per IP address, and throttled to a maximum of 15 per minute. | ||||

| 2. | Public and government access resembles a browser like Google Earth that would allow users to explore an area and read story units from those locations. Such a format also includes a “rest service” so governmental users can overlay the story units with their in-house GIS databases so they can see how their data—such as for transportation, real estate, and economic development—overlaps the story data. The rest service data will be similarly throttled as in option 1. | ||||

| 3. | Research access allows twenty times the daily access of the other two options to facilitate consolidating ethnographic data while conducting research. Research projects will have to originate from a university that has be granted research access via an application process. This will require the ethics oversight department of the university to oversee and guarantee the use of the archive by their associates. Research access allows the university associates the right to submit a research proposal. The research proposal will include the names and verified contact data of the researchers, the title and goals of the project, the requested number of story units with justification, and a signed agreement citing civil laws and stipulating damages to be assessed should the agreement be broken. All publication of story units require the citation of the story unit code to allow data auditing by either the storyteller, archive holder, or other researchers. | ||||

| Governance: | |||||

| 1. | Ledger Council (LC) oversees operations and management of the Nİ. The LC is the composed of representatives of the individual institutions that provide ledger hosting. Associated bylaws dictate which institutions can be ledger hosts, their application and vetting process, and requirements and benefits. The LC will convene once a year for general policy review, and on an as-needed basis when evidence arises of gross-violation of the ledger policy. The LC will have status as a legal body. | ||||

| 2. | The Ethics Board members are contract researchers hired by the LC to evaluate research requests and research membership applications. | ||||

| 3. | The Traffic Analysis Office (TAO) employees are hired by the LC to monitor the data flow to different IPs as well as to develop algorithmic analysis of data access patterns to identify bad actors attempting to aggregate the stories of large geographic areas. They will have the authority to disable all access for up to twenty-four hours if they believe they have detected fraudulent activity. | ||||

| Ethical Bond | |||||

| Two operational philosophies of narrative infrastructure: | |||||

| 1. | Data Protection by Design | ||||

| Nİ is structured on a foundation of Intellectual Property Control. When a living storyteller gives permission to use their story to build narrative infrastructure, they will be assigned an access code by the Nİ notification system within CHORUS to manage their intellectual property. The notification system would assign codes for institutional archives, directing similar notifications to the archive manager’s email address.

Whenever a story unit is published publicly on the Internet, the original storyteller or archive holder (the “data controller”) is notified via email. The data controller is informed of the web address where their story was used, and provided with the option to retract their story if they so desire. Once done, a retraction is irreversible. Future use of their story will generate an automated request for take-down demand from the Ledger Council. Academic research that used and cited story units will not be subject to take-down requests, but future examination of their works cited will reveal the take-down request and the reason for which the take-down request was made—which could be the research paper in question. |

|||||

| 2. | The “Small Data” Philosophy | ||||

| The archive is built and encrypted to disallow aggregation of large data sets. Access to large amounts of story units would allow for re-aggregation of the separated story units, and effectively de-anonymize the data—violating the agreements with many of the storytellers who have contributed to the Nİ. This provision is written expressly to thwart machine-based processing. The Nİ archive should never be perceived to be a large data set of any type. It is meant to be used on a discreet local level, not to develop generalities beyond the spatial scope of a community of in-person associating adults. Any attempt to aggregate the data will be met with immediate suspension of the accounts in question, temporary suspension of the archive as a whole, and legal action against violators of the terms of use agreements, as appropriate. | |||||

| The Fundamental Components: What we need to build | |||||

| Proscenium | Gathering Data with Proscenium | ||||

| The Proscenium interface is used to curate collections of assets that can be explored with a GPS enabled smart device, with options for displaying interlinking (“tours”) and appending the user’s own commentary. It will have a recording interface for conducting interviews that is designed from the beginning to be map-based. It will include standard information and consent forms for collecting those stories from storytellers. There will be the option to import data from other sources, and a function to build a task for UNİ Coders.

Proscenium is a knowledge framework interface that allows members of the public, creative industry professionals, and tourism facilitators to curate geo-fenced maps for real-time exploration of the knowledge framework, both from the desktop application and while walking in neighborhoods coded with digitized stories. It will be compatible with other archives of digitized cultural assets that include visual, textual, and video media. Users will be able to build a project within Proscenium that will allow them to isolate story units by date range and geographic location. All story units can be coded (similar to adding a keyword), then organized by keyword and displayed uniquely to suit the user’s inquiry. The spatial extents of each story can be adjusted, but doing so will automatically add a notification of the deviation from normal story range to all reports generated with the modified data. |

|||||

| UNİ Coders | Processing Data with UNİ Coders | ||||

| To facilitate the distributed and anonymous processing of the oral histories, a micro-contract website will be available to universities to allow their students to work to anonymize the story units and improve the transport network map around those story units. Their work will be double-blind validated to ensure that the data is properly processed. Those students will then be paid out of operational budget of the LC. | |||||

| CHORUS | Data Archiving and Management with CHORUS | ||||

| The Cultural History and Oral-history Unification System (CHORUS) will provide the back-of-house consolidation and management of the story units and other digital cultural heritage assets that are uploaded to the archive. The public-facing distribution of CHORUS is provided by Proscenium.

CHORUS is the archive itself, this is the software what will verify encryption, conduct traffic analysis, issue notification of publication, and throttle access as necessary. |

|||||

| CALL TO ACTION | |||||

| Narrative infrastructure is all around us right now, but it is not useful until it is mapped. The exercise of mapping stories—utilizing spatial narratology—is not challenging or complicated. For the benefit of all people alive now and those who follow us, we propose the following actions be legislative priorities: | |||||

| 1. | Build Proscenium: Story collectors and archivists need an application to gather and share stories. | ||||

| 2. | Design the UNİ Coder web platform in partnership with EDURoam and other allied agencies to leverage the academic community in support of Narrative İnfrastructure. | ||||

| 3. | Design the CHORUS archive with its core enabling encryption and distributed public ledger framework. | ||||

| 4. | Fund and convene the Ledger Council so the governance of Narrative İnfrastructure can commence. | ||||

| Feel free to adapt the letter below to email to your political representatives: | |||||

| Join the conversation: | Dear Citizen agency has been in decline for decades; so, I want your office to take action to build narrative infrastructure. We are all surrounded by stories—nothing happens without someone telling a convincing story. Help us use our stories to lead and guide our communities. We all wish we could have impact on local politics and development, but it is time consuming. Narrative infrastructure is a PUBLIC INFRASTRUCTURE that allows individual community members to record their oral history and demonstrate those stories on a common map. Our life stories are what make an authentic "sense of place” and we believe these mapped stories should guide decision makers. Meaningful community life starts with a story: • When our stories are available to you, you can make better-informed decisions on policy. • When our stories are available to development interests, they can mitigate their risks by supporting local community sentiment. • When our stories are available to each other, we can increase our empathy for our neighbors despite language and cultural differences. • When our stories are available to our children, they can make their own new stories in continuity with local memory. • When our stories are available to our public servants and consultants, they can build a meaningful shared world. Anyone can collect stories for narrative infrastructure. Everyone can use stories to better understand local conditions. We need four things to build narrative infrastructure as public infrastructure: 1. PROSCENIUM: A story collection tool that also allows for public exploration and use by different groups (e.g. businesses, NGOs, political interest groups, public servants, scientific researchers). 2. UNI Coders: A story parsing process to provide anonymity and geograpic data when requested. 3. CHORUS: An encrypted archive that utilizes a distributed public ledger to ensure the individual stories are not manipulated or deleted. 4. Ledger Council: A governing council overseeing a traffic analysis office and ethical use board. Once these four components are built, the narrative infrastructure will enhance citizen agency. This is a low-cost, long-term improvement for democratic engagement around the world. It facilitates any human being who can tell a story to convey it to someone with access to the Internet. I urge you to act today: make the building of narrative infrastructure a high legislative priority. Introduce legislation. Support narrative infrastructure legislation. Do this, and build something that will change the world for the better. For more information visit the narrative infrastructure website: www.narrativeinfrastructure.org Sincerely, of *where you live* |

||||